EWAS Analysis in MVP

1 Million Veteran Program

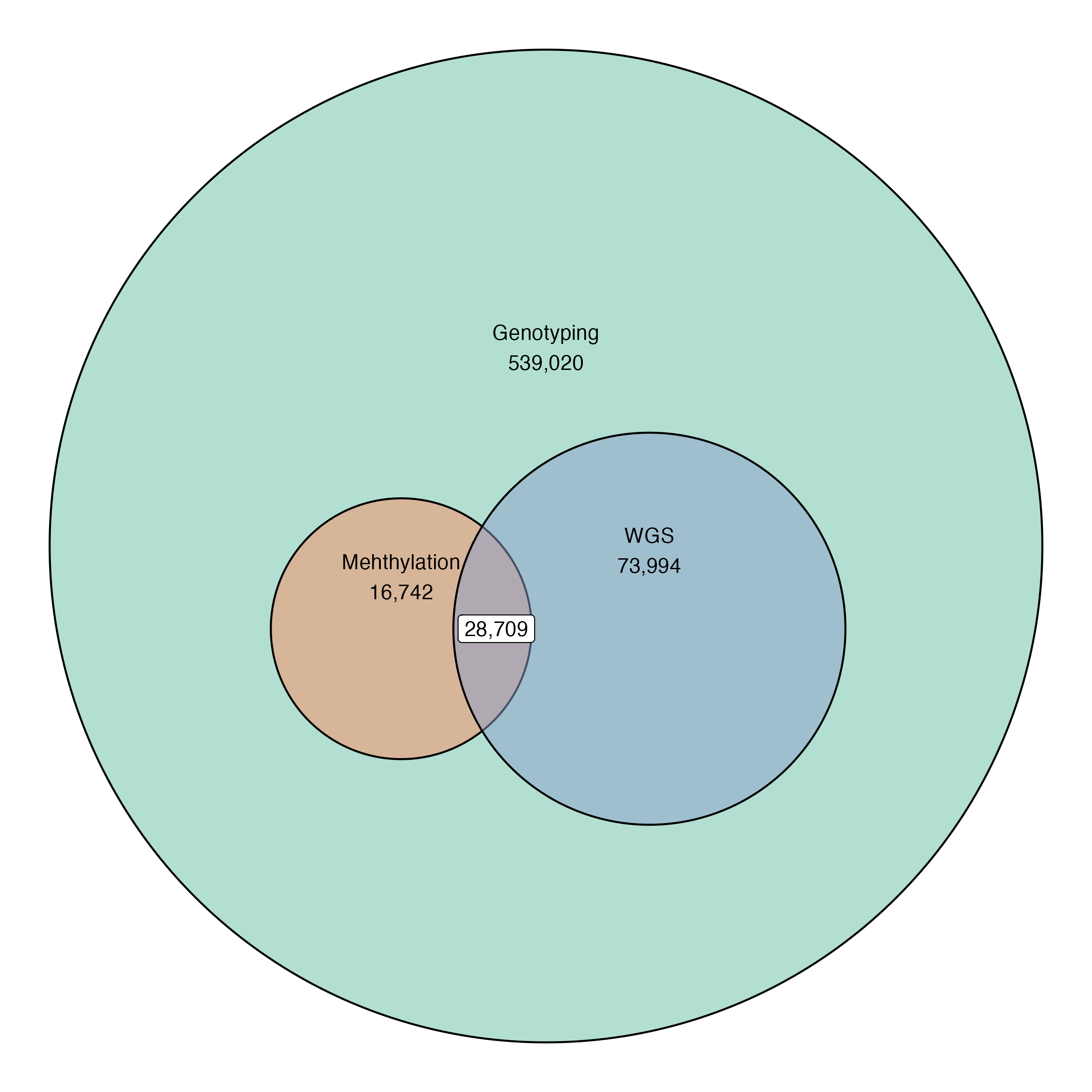

Current data release:

539,020 Individuals

28,709 (~64%) with whole genome sequencing

45,460 individuals with methylation data

Among these, ~40% are T2D.

2 Problem Setting

Assume we have \(N\) subjects, \(d\) covariates (including the intercept), and \(M\) CpG sites or probes. EWAS requires repeatedly estimating the model:

\[ \boldsymbol{\beta}_j \sim \mathbf{x}\alpha_j + \mathbf{Z}\boldsymbol{\gamma}_j + \boldsymbol{\epsilon}_j \]

where \(\epsilon_{ij} \sim \mathrm{N}(0, \sigma_j^2)\) for \(j = 1, \dots, M\). The regression coefficients \(\alpha_j\) are the parameters of interest, and parameters \(\boldsymbol{\gamma}_j\) are nuisance parameters. Concatenating the \(M\) regression models together, we have:

\[ \boldsymbol{B} \sim \mathbf{x}\boldsymbol{\alpha}^\top + \mathbf{Z} \boldsymbol{\Gamma} + \mathbf{E} \]

Let \(\boldsymbol{\Theta} = [\boldsymbol{\alpha} : \boldsymbol{\Gamma}^\top]^\top\) and \(\mathbf{W} = [\mathbf{x} : \mathbf{Z}]\). The least squares estimates are straightforward: \[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{\Theta}} = \left(\mathbf{W}^\top \mathbf{W}\right)^{-1} \mathbf{W}^\top \boldsymbol{B} \]

and \(\widehat{\sigma}_j^2 = \frac{1}{n-d}\sum_{i=1}^N b_{ij} - \mathbf{w}_i^\top \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\).

In the case of MVP, we have roughly \(M \approx 750,000\) and \(N \approx 45,000\), which would require over 250 Gb of memory to store all at once.

3 Methylation Data in MVP

In MVP, \(\boldsymbol{\beta}_1, \dots, \boldsymbol{\beta}_M\) have been stored in the HDF5 file format, which stores each chromosome as a separate table. Suppose we have an arbitrary chromosome \(\mathbf{B}^k\).

\[ \mathbf{B}^k = \begin{bmatrix} \mathbf{B}_{1,1}^k & \cdots & \mathbf{B}_{1, m_k}^k\\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots\\ \mathbf{B}_{n_k,1}^k &\cdots &\mathbf{B}_{n_k, m_k}^k \end{bmatrix} \]

The chromosome with the largest amount of data, chromosome 1, is stored in 8 chunks, where the largest chunks are square matrices roughly 4 Gb in size (\(n_1 = 4,\, m_1 = 2\)).

The HDF5 file format stores each submatrix \(\mathbf{B}_{i, j}^k\) as a contiguous chunk in storage,

Access to any data stored within a particular chunk requires decompressing the entire chunk.

- Generally, decompression is a very slow operation, if possible, we would like to never decompress any chunk more than once.

4 Sufficient Statistics

Fortunately, the problem structure of EWAS almost lets us do this exactly, the regression coefficients estimates \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\Theta}}\) only require:

The Gram matrix \(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{X}\)

The \(d\) by \(M_k\) matrix product \(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{B}^k\)

- \(d << N\) so we have no problems allocating the full array in-memory

Taking a closer look, we can represent \(\mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{B}^k\) as summation,

\[ \mathbf{X}^\top \mathbf{B}^k = \begin{bmatrix} \sum_{i=1}^{n_k} \mathbf{X}_i^\top \mathbf{B}_{i, 1}^k & \cdots & \sum_{i=1}^{n_k} \mathbf{X}_i^\top \mathbf{B}_{i, n_k}^k \end{bmatrix} \]

The term \(\sum_{i=1}^{n_k} \mathbf{X}_i^\top \mathbf{B}_{k, i, j}\) only depends on the \(j\)-th block column slice of \(\mathbf{B}\). Thus, we have exactly what we wanted, and only need to access one chunk of \(\mathbf{B}^k\) at a time.

Handling missing values in \(\mathbf{B}^k\) complicates this, but in the simple case of mean imputation, we still only need to store \(n_k\) chunks simultaneously.

For inference, we also require storing the residual sums of squares for each column, but this is only a vector of length \(M_k\)

5 Existing Implementation

The script EWAS.R in GENISIS is implemented using the meffil and bacon R packages, but in particular meffil does not take advantage of the inherent structure in the problem.

The default data access is in column slices of width \(5,000\), this requires decompressing every chunk up to 9 times due to a mismatch in how the \(\beta\) values are stored on-disk.

meffilmakes an empirical Bayes adjustment for the standard error \(\mathrm{SE}[\widehat{\alpha}_j]\), but in large sample sizes, this adjustment is unncessary.- This adjustment is also subtly incorrect when passing \(5,000\) sites at a time, and may induce bias in EWAS test statistics

Tries to load an entire chromosome into memory at a time, which is generally infeasible

baconconstructs a 3-component mixture approximation to the empirical null distribution of the test statistics but only depends on summary statistics, so it is quite fast

6 New Implementation

Only accesses at most 2 chunks simultaneously avoids high memory requirements

Peak memory usage is approximately 25 Gb for full EWAS on BMI

Longest job submission only takes 15-20 minutes to run EWAS on Chromosome 1 (the largest number of probes)

Parallel job submission over all chromosomes only takes 15-20 minutes, i.e. the time it takes for the longest running job to finish

Estimation of the empirical null using

baconcan be done by aggregating per chromosome summary statistics

7 EWAS for BMI

EWAS for BMI was conducted separately for the EUR and AFR self-reported ancestry, as well as all MVP subjects pooled together.

EUR: \(N = 27,137\)

AFR: \(N = 11,361\)

All MVP: \(N = 44,850\)

Model:

\[ \begin{aligned} \beta &\sim \text{BMI} + \text{sex} + \text{age} + \text{age}^2 + \text{cell composition(Houseman)}\\ &\qquad + \text{Scanner ID} + \text{Duration of Sample Storage}\\ &\qquad + \text{Technical PCs} + \text{Genomic PCs} \end{aligned} \]

8 EWAS for Glycemic Exposure

Hypothesis: HbA1c has a cumulative effect on DNA methylation levels

EWAS covariates of interest: historical HbA1c level 5 years prior to DNA methylation sample collection:

Sample Size: \(N = 13,567\)

Model:

\[ \begin{aligned} \beta &\sim \text{Mean HbA1c} + \text{sex} + \text{age} + \text{age}^2 + \text{cell composition(Houseman)}\\ &\qquad + \text{Scanner ID} + \text{Duration of Sample Storage}\\ &\qquad + \text{Technical PCs} + \text{Genomic PCs} \end{aligned} \]

9 Further Analysis

Complete case analysis instead of mean-imputation

Stratify by baseline or pre-baseline HbA1c level

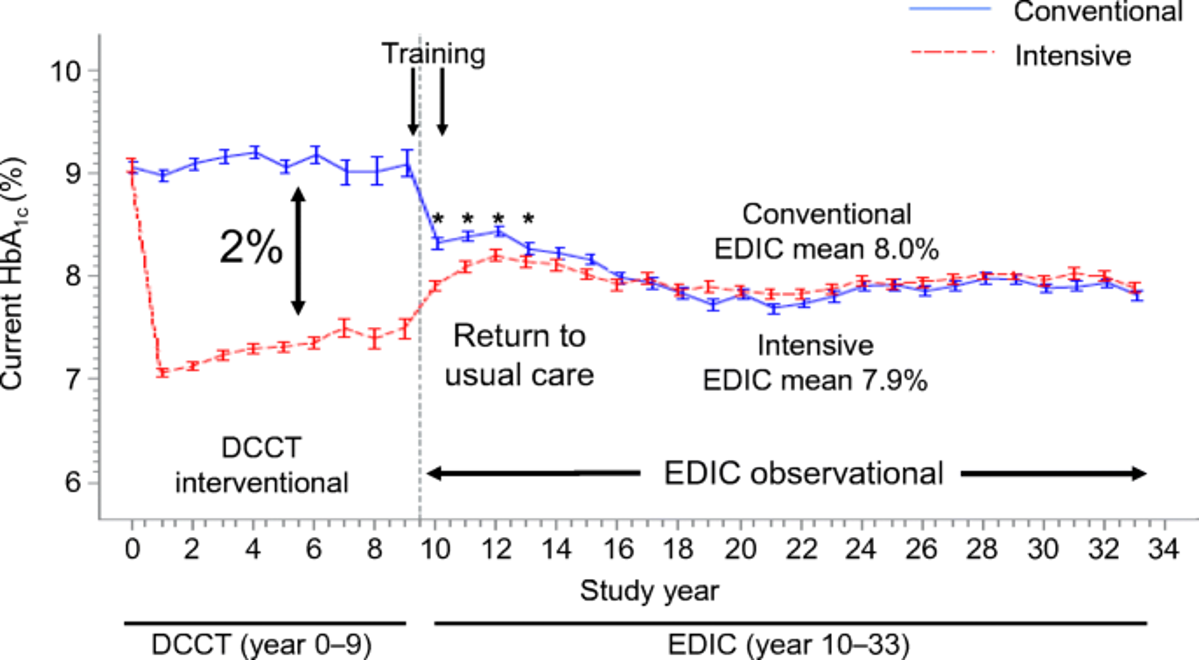

Intensive treatment during DCCT resulted in an average of 7.0% HbA1c over the entire trial

Convential treatment during DCCT resulted in an average of 9.0% HbA1c over the entire trial

However, patients were randomized to each condition, which may not be comparable to MVP cohort

Stratify by race/ethnicity

- The sample in DCCT was 96% Caucasian, which is very different from MVP

Stratify by relative time of diagnosis with Type 2 diabetes (recently diagnosed vs. not recently diagnosed)

References

10 Background

Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT): Type 1 diabetic subjects (\(n=1,441\)) comparing intensive vs conventional diabetes management.

Intensive care reduced the risk of:

Diabetic retinopathy by 76%; and advancement of eye disease by about half (54%), in people with some eye disease at the beginning of the study

Diabetic kidney disease by 50%

Diabetic neuropathy by 60%

Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC): Long-term monitoring of DCCT participants has found that the differences in outcomes between both groups has persisted over long-term tudy

11 (Chen et al. 2016) DCCT-EDIC

- Examined DNA methylation data collected in the DCCT-EDIC study using two sets of samples:

| Samples | Case | Control | Time of Sample Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole Blood DNA | 32 | 31 | EDIC Study baseline (1991-1993) |

| Monocytes | 31 | 30 | EDIC Study years 16-17 (2009-2010) |

where cases and controls were defined by:

Cases: DCCT conventional therapy group subjects with mean DCCT HbA1c > 9.1% and showing retinopathy or albuminuria progression by EDIC Study year 10.

Controls: DCCT intensive therapy group subjects with mean DCCT HbA1c < 7.3% and without complication progression by EDIC year 10.

Findings:

- after adjustment, they identified 135 hypo-methylated CpG sites and 225 hyper-methylated CpG sites in cases vs controls.

- partly due to the differing cell-types in baseline and year 16-17 samples, they only identified 4 hypo-methylated and 8 hyper-methylated sites that were persistent.

12 (Chen et al. 2020) DCCT-EDIC

A larger cohort of 499 randomly selected participants, 125 from each of the DCCT groups (Primary Intensive, Primary Conventional, Secondary Intensive, Secondary Conventional)1

Out of 815,432 CpG sites, identified 43 CpG sites associated with mean-DCCT HbA1c (how long and far back?) at a false discovery rate of <5%, which was further reduced to 11 CpG sites after Bonferroni adjustment (\(\alpha = 0.05\)).

Findings:

- “best combinations of multiple CpGs” selected from the top-ten HbA1c-associated CpG sites could explain the association between mean-DCCT HbA1c and the risk of developing diabetic complications, including

- 71% for proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR)

- 73% for severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy (SNPDR)

- 68% for clinically significant macular edema (CSME)

- 97% for albumin excretion rate >300 per 24h (AER300),

- 92% for eGFR <60 mL min–1 per 1.73 m2 (GFR60)

- 84% for eGFR slope.

- 4 HbA1c associated CpG sites as having methylation quantitative trait loci (meQTLs), from which one CpG site (

cg08309687) had an identified causal effect on GFR60 development.

- “best combinations of multiple CpGs” selected from the top-ten HbA1c-associated CpG sites could explain the association between mean-DCCT HbA1c and the risk of developing diabetic complications, including

Footnotes

One subject was excluded due to large differences in estimated white blood cell composition.↩︎